The damage we do in the hustle for "good"

We've been on a long journey, and there's lots of unpacking to do

Dear Writer,

Some years back, when I was first beginning to discover that my childhood was good and fucked and that everything I thought I knew about the world wasn’t necessarily, you know, actually true, I started to take a look at my need to be a “good” person all of the time, and had my first inklings about how our ideas of goodness and badness—like our ideas of perfection and imperfection—are maybe not appropriate, or helpful.

It started with a belief I’ve held for most of my life that I needed to be a “good” person, and how I always felt like I was failing at that if I did anything that wasn’t “perfect.” In my constant striving and failing to be “good,” I inevitably became frustrated and did “bad” things—yelled at the kids or someone in customer service, snapped at a friend or a family member. Occasionally… very occasionally… I would do something just for me, without piggybacking it on someone else’s needs or wants (like if the kids wanted ice cream, I’d have ice cream with them, but only if they wanted it, shit like that.) When I did something for myself, my internal response was a debilitating tsunami of guilt and shame, which are two emotions that were used to control me when I was young and which still result in bad mental weather for days when I experience them now.

Inevitably, in response to the tsunami, I would spiral back to trying to be “good” all the time; a response which was, in fact, very, very bad for me.

It’s been about 14 years since I began the process of waking up from all of this, and I’m only just now really starting to unpack what “good” and “bad” even mean.1

Space is limited for my Year of Writing Magically workshop. Be sure to apply today! Applications close Feb. 12.

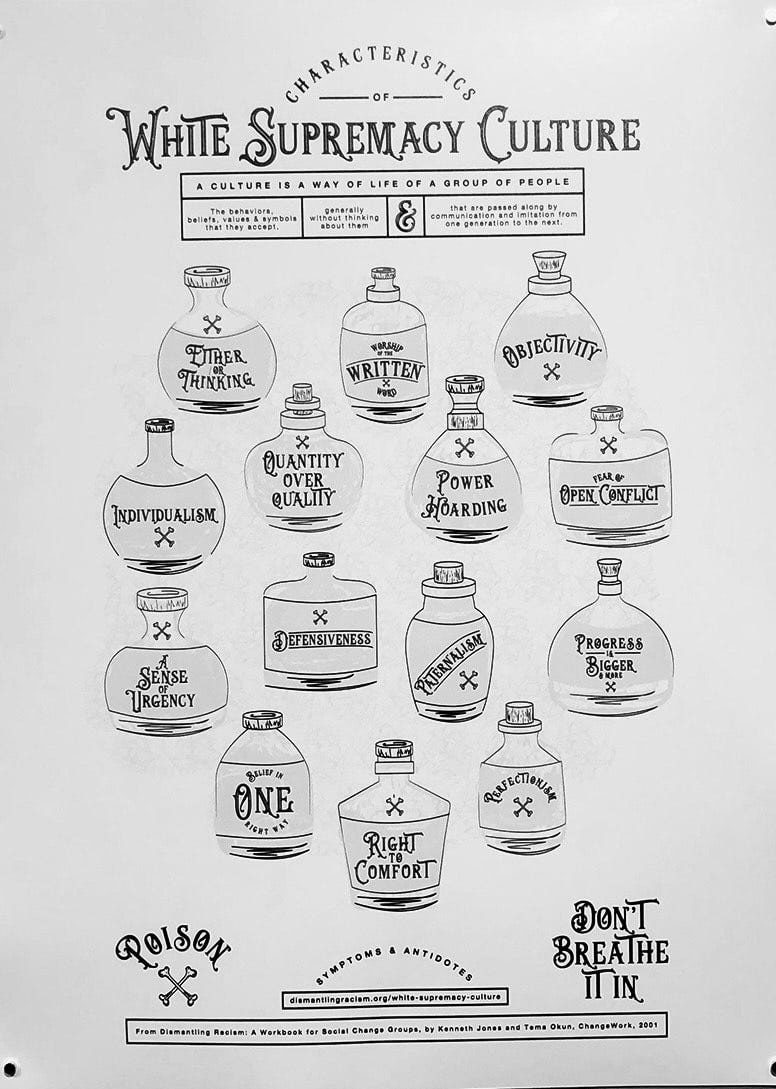

One of the absolutely most helpful things I’ve come across in a decade-and-a-half of stumbling across incredibly helpful things is this poster, drawn for the Dismantling Racism workshop by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun (now a full website) by artist Melanie G.S. Walby:

SIDE NOTE: I have been sitting in contemplation with this amazing art since I first saw it in a TikTok video sometime last year. I have realized that my idea of “goodness” came from a culture that was not interested in my wellbeing… or in anything, really, other than the consolidation of power and wealth in the hands of a select group.

I highly recommend, if this material is unfamiliar to you, to take a bottle a week and journal on it. Journal privately. If anything here makes you mad, be mad. Don’t try to be “right” about anything. Just discover where you are.

What's funny is that one of the go-to examples of binary (either/or) thinking are the concepts of "good" and "bad." The endless hustling for our value by being “good” all the time is inherently faulty thinking, and ultimately does damage to both us and the people around us.2

So, back in the day, when I was just starting to have this idea that the endless and doomed pursuit of being “good” all the time made “good” a broken concept, I had a strong resistant reaction to the idea, and it went a little something like this:

Of course being ‘good’ is good! You can’t just go around doing whatever you want without consideration for the impact it might have on others. So being ‘good’ has to be good, and being anything other than ‘good’—self-sacrificing and always thinking of others—by definition must be ‘bad,’ right?

This is an example of either/or, binary thinking, where if you dismiss one concept—good—then that means that you are automatically, on the whole, in the territory of its opposite—bad.

The problem wasn’t really even in the concepts of good and bad themselves, but rather in the associations we as a society placed on good and bad, and the way we binary’d the fuck out of it. Good was anchored for me in selflessness; you gave and you gave and you gave and you gave and you never asked for anything back and if there was a package of cookies, you took the broken one always so that others could have the whole ones. Bad was anything other than constant self-sacrifice and denial.3

Now, if you sit with that for a minute and find yourself nodding along, like, “Well… yeah,” then you’re where I was. For me, at that time, being “good” meant sacrificing what was best for me so that I could always choose whatever was best for other people, no matter what. It didn’t matter if the net damage to me was a million times greater than the net benefit for whoever my denial was in service to; I always chose to take the hit. It didn’t matter how tiny that choice was, either; even if it was as meaningless as a broken-cookie choice, I always chose the broken cookie or suffered a tsunami afterward.

Then, one day, when I was contemplating how frustrated and angry I was all the time, I realized that my constant sacrifice in servitude to “other people” was faulty because I, too, was a person. I was someone else’s “other people” and yet no one was sacrificing for my minor, momentary whims, let alone my best interests4. Sometimes, this was because they were not raised as women, and thus had not been socialized toward constant sacrifice. More often, it was because I simply would not have it. I actively surrounded myself with people who would not fight me on this, because I could not fight it within myself.5

The idea that it was my job to be “good” and self-sacrificing was faulty. It was an idea that was born at the intersection of Either/Or Thinking and Individualism, and it’s instilled in us to the benefit of white supremacy and patriarchy.

And it’s in our stories.

It’s all over our stories.

We have been working, until recent years, with a lot of pure White Hats and pure Black Hats,6 where we need our heroes to be 100% good and our villains to be 100% bad. This actively prevents us from acknowledging the bad things that our heroes do (remember how Indiana Jones slept with a 15-year-old child when he was in his mid-twenties?) which means that we are failing to think critically about goodness and badness because our stories don’t allow for it.

Let’s even flip that script; let’s talk about our villains. Remember Walter White in Breaking Bad? There are many people who read that story as a good man gone bad, sure, but they admire him anyway. He’s trying to make money for his family (true) and he’s out of options (probably not as true as some reads make it seem, but let’s go with that, sure.) But here’s the thing; Walter White is not a good man gone bad; he’s a weak man who found access to power, and then did terrible things with that power.

Now, I’m not gonna lie, I think Breaking Bad is a great show, but a lot of people see a good man forced to do terrible things by a circumstance outside of his control and that is not what that show is. Yes, the cancer is outside of his control, but his response to his anger and weakness is to grasp power and do severe harm with is his active choice so… this is not a good guy. What’s funny is that the text even seems to know this, and in my read does not rubber-stamp Walter’s behavior as heroic. But we are so primed by centuries of storytelling to side with the white guy that even when the text appears to be saying, “Hey, this is not a good guy,” we often cannot see white male protagonists as anything other than heroes. We’ll allow a little rogue hero here, a little anti-hero there, but when the curtain comes down, we love them as heroes nonetheless.

Lather, rinse and repeat that argument with Mad Men.

This is an argument you can reverse if the protagonist is a woman or, even more starkly so, if they are Black, Indigenous or another person of color. No matter how good they are, if they are not serving or being “saved” by dominant power structures, we struggle to see them as good.

All right; this is where you come in. This is where the new wave of stories comes in. This is where we take our knowledge and power as storytellers and break the cycle, but we can’t do that until we start allowing ourselves to see the nuances in what constitutes “good” and “bad” in the world around us. Stop thinking in terms of heroes and villains, and start thinking in terms of protagonists who are not perfect, and antagonists who are not wholly evil.

All you need for a story to work narratively is a protagonist who wants something, and an antagonist who wants something mutually exclusive. One does not have to be bad or evil; the other does not have to be good or virtuous. Why readers might root for your protagonist to win can be complicated; why readers might root for your protagonist to lose, and that loss being a net positive for your protagonist despite them heartily resisting it all the way, can be really fun to write.

Walk in the sand, and start swiping your feet through the deep lines we’ve drawn between good and evil. Work in the nuanced space in-between. Try to battle your own binary thinking, and then bring the fruits of that battle into your work. You will be amazed at the richness you’ll find there. Lots of writers are already doing this work, and but it will take many more of us telling many more of these stories for us to finally start to crack through these culturally-instilled notions that do not serve any of us.

The more of those stories we have out there, the more we dismantle the power structures that are actively hurting all of us7. That’s fun, crunchy work to do, and I say we do it.

Everything,

L

Now, your mileage may vary on this. Your definitions of what is “good” and “bad” will likely be different from mine, but if you’re ready to handle the destabilizing effect of said unpacking, I recommend it.

If you’re wondering, “What does this have to do with writing?” hang in here. I will get to it. Also, everything that has to do with being human ultimately has to do with writing.

I won’t get into how this self-sacrifice and denial is mostly expected of women, and doubly so of mothers… that’s a whole ‘nother topic.

I can’t even go into how it makes the people who genuinely love you feel to constantly have their tiny benefits placed above your tremendous detriment. Again… whole ‘nother topic.

When you realize that your expectations of yourself are different from your expectations of other people, that’s a red string you can follow to big realizations. It will piss you off, but follow it anyway. In the long run, it’ll be worth it.

I doubt this mapping of white and black to good and evil is an accident, but I haven’t done the research today. Go check it out and bring back anything you find.

White supremacy hurts white people. Patriarchy hurts men. There is no misandry or white hatred here. Love for everyone demands dismantling systems that hurt everyone.

Wow... just wow. I'm going to be unpacking this for a while. Thanks for giving writer Nan something to consider as I start this new novel.

Outstanding piece with virtually unlimited implications. Thank you!